Blog Post #4 – Exploring Soft Robotics for Archaeology: Choosing the Right Touch for Fragile Artefacts

When we think of archaeology, we often imagine skilled hands carefully brushing away centuries of dust from fragile artefacts. But what happens when those hands are replaced by robotic ones? This is the challenge we face in AUTOMATA: creating a robotic system capable of documenting and analysing archaeological objects without compromising their integrity.

AUTOMATA is a European research project aiming to automate the digitisation of archaeological artefacts—especially ceramics and stone tools—so they can be studied and preserved in unprecedented detail. To achieve this, robots need to do something surprisingly difficult: pick up objects safely. Unlike industrial parts, archaeological artefacts vary enormously in shape, size and fragility. A rigid metal gripper could easily damage them. That’s why we explored soft robotics, a branch of robotics that uses flexible materials and adaptive designs to mimic the gentle touch of human hands.

Our task was to evaluate existing technologies and identify the most suitable solution for AUTOMATA’s needs. We focused on two promising candidates: the SoftHand and the SoftClaw. Both were originally developed for other applications, but their adaptability made them strong contenders for handling cultural heritage objects.

SoftHand: Inspired by Human Dexterity

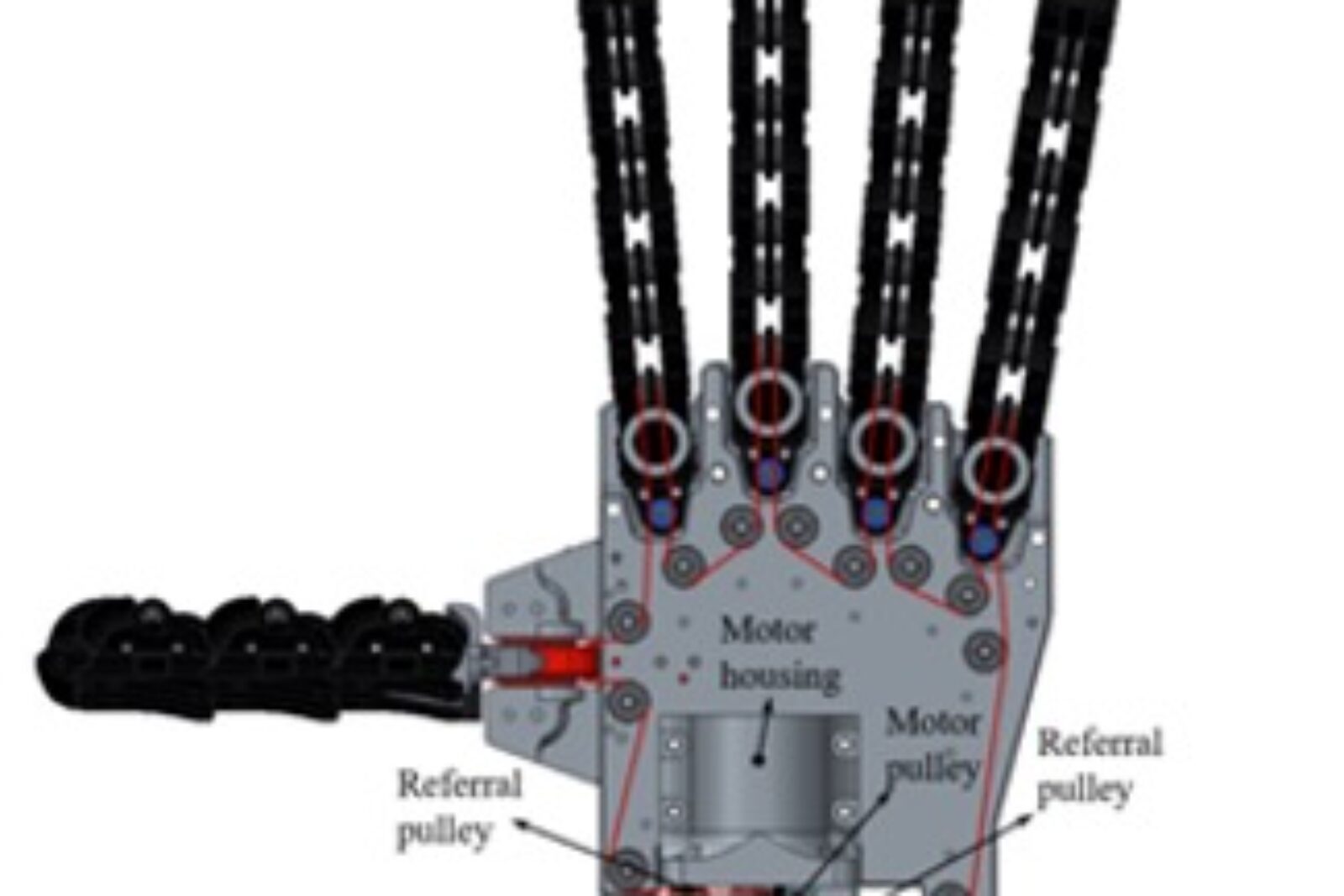

The qbSoftHand (Fig. 1) is a robotic hand designed to replicate the natural adaptability of human fingers. Instead of multiple motors and complex programming, its operation relies on a motor with a pulley that winds a single tendon running through all its 19 joints. When the fingers close, they naturally conform to the object’s shape (just as our fingers do) without needing advanced sensors or algorithms. This makes the SoftHand ideal for artefacts of different sizes and contours.

Fig. 1: qbSoftHand

The hand acts as a large differential mechanism where power flow is transmitted in series to all joints. If some joints are blocked (for instance, by external constraints or by the grasped object), the tendon continues to run on the idle pulleys of those joints, still transmitting power to the other free joints. This design allows the fingers to adapt to the shape of objects, similar to human fingers. The peculiar adaptivity of the SoftHand is intrinsic to its mechanical design and is not dependent on complex control strategies.

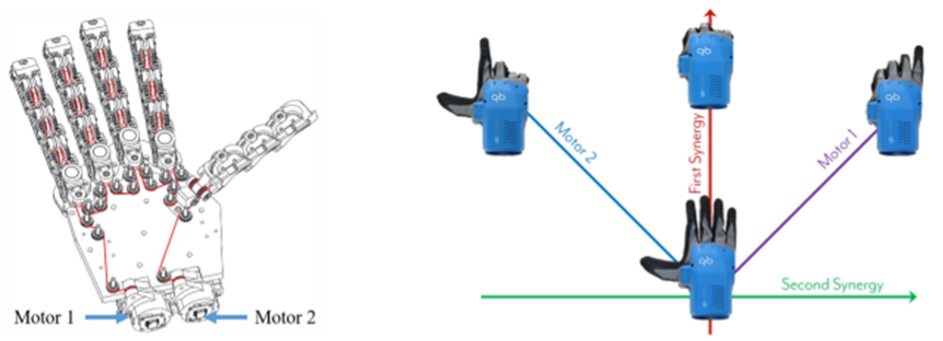

Its evolution, the SoftHand2 (Fig. 2), adds a second motor, enabling more refined movements such as pinch grasps, essential for small lithic fragments. And for even more delicate tasks, there’s the SoftHand Mini, a scaled-down version designed for smaller objects.

Fig. 2: qbSoftHand2: left – transmission system with two motors; right – the two synergies of the hand are shown

SoftClaw

While the SoftHand focuses on adaptability, the SoftClaw brings precision and control through variable stiffness technology. In simple terms, this means the gripper can change how firm or soft its grip is. Imagine a tool that can cradle a fragile ceramic shard with a gentle touch, then hold a heavier piece securely -all without damage. That’s the SoftClaw. Its two-finger design may look simple, but its ability to adjust force makes it a strong candidate for archaeological applications.

Fig. 3: qbSoftClaw with deflection control: soft grasp on the left and strong grasp (high deflection reference) on the right side.

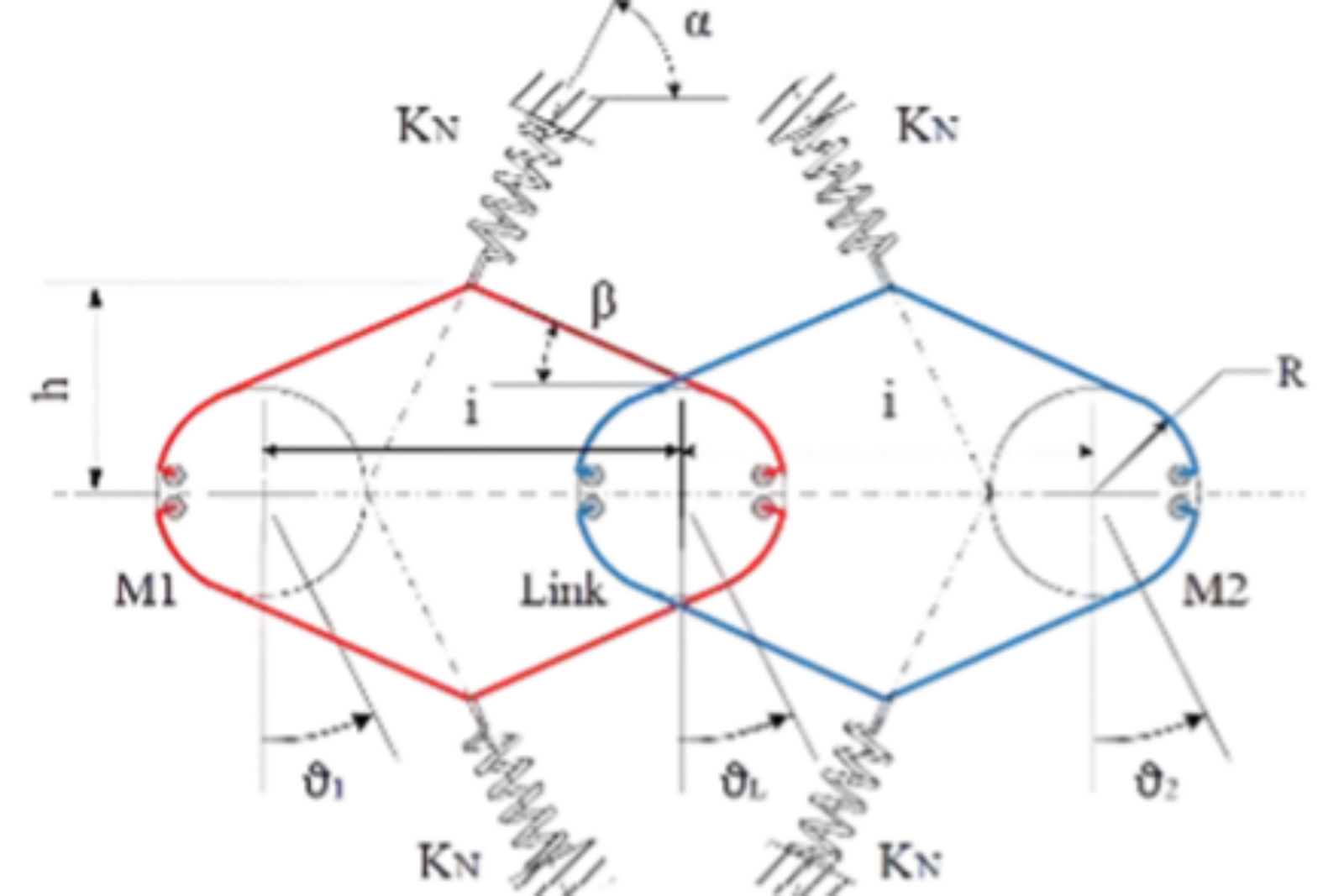

A low-level controller has been implemented on-board. It controls motor positions θ1 and θ2 (Fig. 4) according to the reference inputs: the preset stiffness and the equilibrium position of the output shaft. When the two pulleys rotate in opposite directions, the nonlinear springs become loaded. This results in a change of their working point and thus in a different stiffness. Since the two transmission systems have the same characteristics, this movement does not change the output shaft equilibrium position in the absence of an external load. Conversely, pulley rotations in the same direction move the output shaft equilibrium with no load. The gripper is then able to grasp objects of considerably disparate nature, exploiting the intrinsic mechanical intelligence of its variable stiffness system, without using any type of sensors on the contact surfaces or specific algorithms to control the motors. These aspects make it a versatile, light, economical and easy-to-use device.

Fig. 4: The variable stiffness mechanism that permits the implementation of human-like behaviour for the actuator.

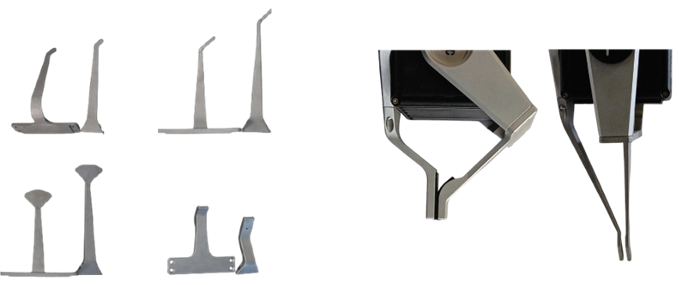

Another important feature is the possibility to customize and easily replace both fingers, so make the gripper as suitable as possible for the desired application.

Fig. 5: Examples of different types of fingers.

Experimental tests

To evaluate these technologies, we conducted experiments using authentic artefacts provided by the University of Pisa. Ceramic fragments ranged from 3 to 10 cm in width, while lithics measured as little as 1.5 cm. These dimensions posed a real challenge, especially for thin and flat pieces.

The results were clear: qbSoftHand2 (Fig. 6) excelled with larger objects and managed smaller ones with reasonable success, though thin artefacts remained tricky. The SoftHand Mini (Fig. 7) showed similar behaviour, confirming that scaling down alone does not solve every problem. The qbSoftClaw (Fig. 8), however, stood out for its reliability. Its ability to maintain an artifact’s position after grasping is crucial for precise sensor analysis, a key requirement for AUTOMATA’s robotic cell.

What’s Next

This evaluation was a crucial step. By adapting existing soft robotics technologies, we are laying the groundwork for a future where robots can handle cultural heritage objects with the same care as human hands. The next phase will focus on refining the chosen design and integrating it into a fully automated system, ensuring that archaeology remains both innovative and respectful of its fragile treasures.

Three experiments were set up as part of D3.1. Several combinations of hardware (robotic arms and soft end-effectors) were used in different operational modes, such as teleoperation, independent grasping, or manual grasping.

Automata Deliverable 3.1 – Soft grippers for archaeology

Fig. 6: Experiments with qbSoftHand2.

Fig. 7: Experiments with SoftHand Mini.

Fig. 8: Experiments with qbSoftClaw and customized fingers.